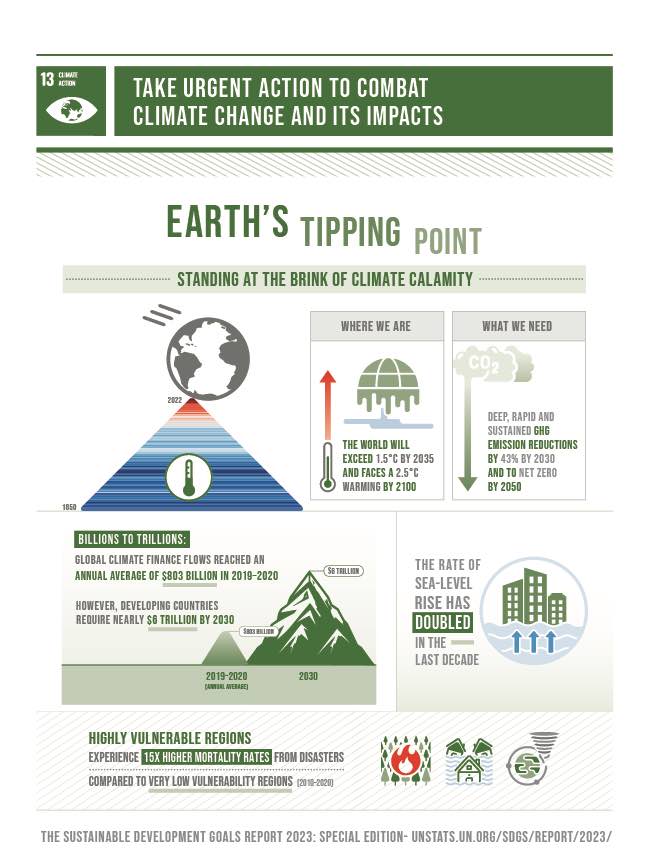

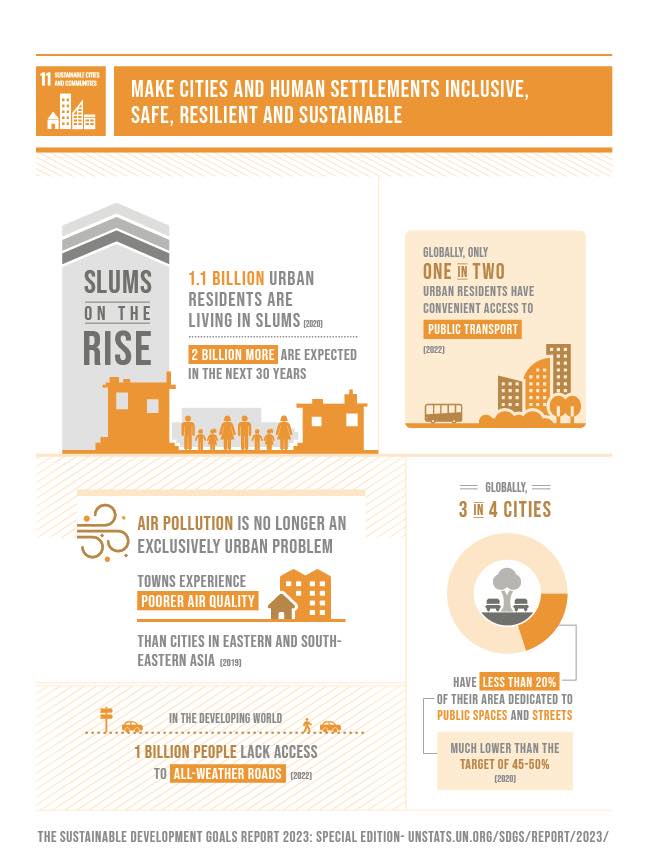

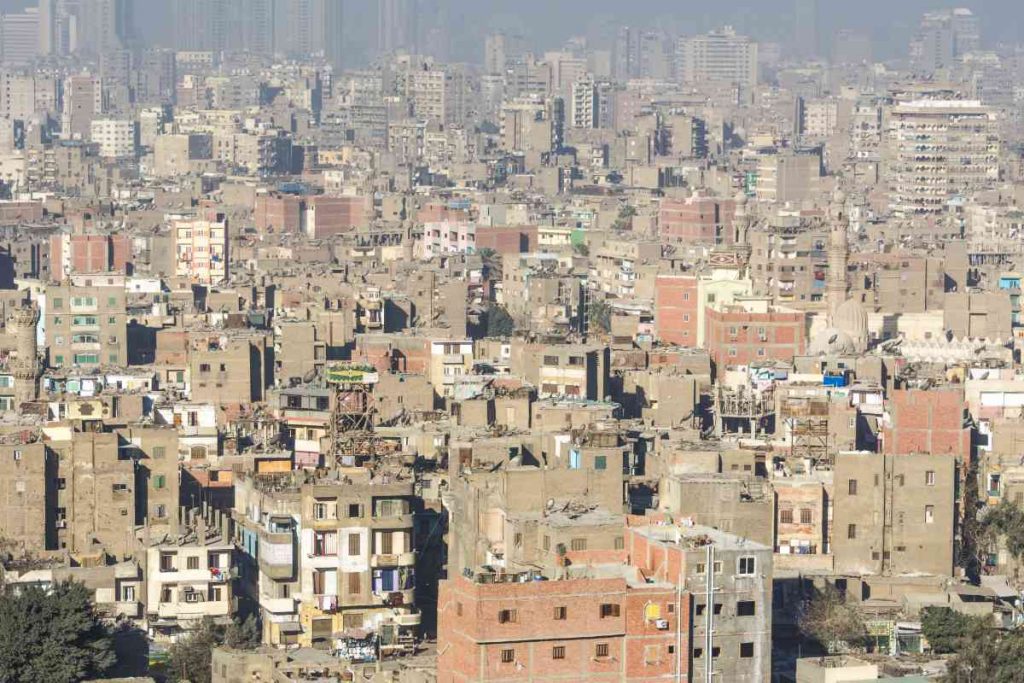

Let’s face it; our future is urban. By 2050 close to 70% of the world’s population will reside in cities, up from 55% (4.4 billion) today. Urbanization rates will rise to 85% by 2100. Presently, cities account for 80% of global GDP, 75% of global CO2 emissions, and 55% of the global population. Asia and Africa, particularly its megacities (10+ million inhabitants), will absorb future growth as the world’s population approaches 9.7 billion by 2050 and 10.4 billion by 2100. Many developing economies across the Global South continue to set aggressive growth targets to match their populations’ high aspirations. The effect of these economic goals will further contribute to hyper-urbanization, a burgeoning middle class, rampant consumerism, and waste. It’s important to note that cities occupy only 2% of the earth’s surface but account for 75% of natural resource consumption. If you solve for the cities nature and biodiversity will follow. Consequently, new, innovative, commercially driven, and inclusive urban-based models must emerge to address future environmental and climate challenges in the dense urban environments of the Global South. In this article, we provide an update on our 2020 article on the progress of micro haulers in New York City and their formalization and inclusion into the city’s waste management ecosystem. We look at what lessons, if any, can be gleaned and transferred to the developing markets to address current and future urban threats. Also, we briefly address the Project ClearSky 2100 micro-infrastructure climate tech platform designed to strengthen climate resilience in the megacities of the Global South.

Managing Waste Streams from Megacities

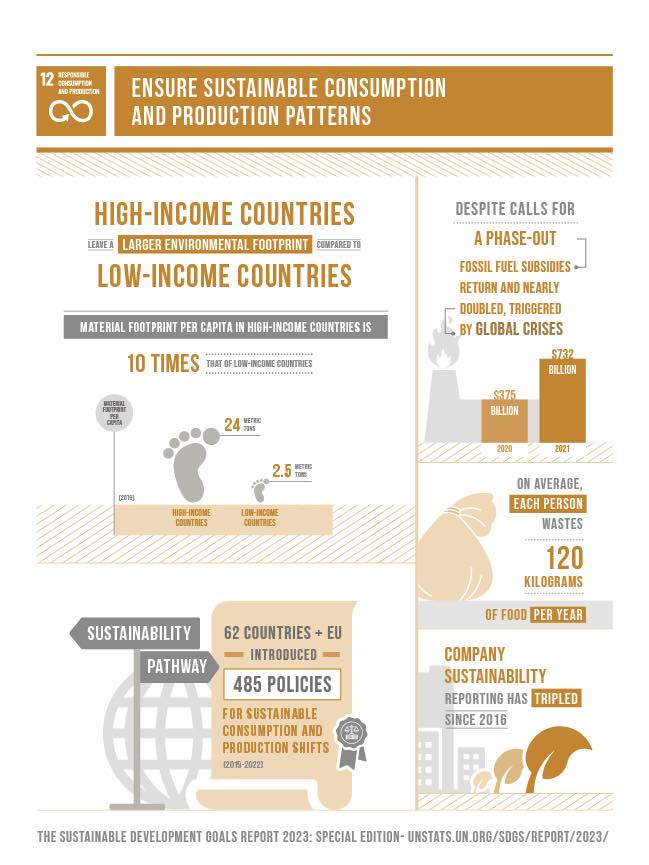

Managing a growing waste stream from excessive urban sprawl, rapid economic development, and population growth remains a crucial challenge for many megacities across the Global South. In 2020 the world generated 2.24 billion tons of waste. Under a business-as-usual scenario, this number will rise to 3.9 billion by 2050. Over 40% of this waste was organic, and at least 33% is managed in an environmentally unsafe manner. Moreover, in developing markets of Asia and Africa, organic rates can approach 80%. In megacities such as Lagos (13,000 tons/day), Metro Manila (12,000 tons/day), Mumbai (11,000 tons/day), and Jakarta (7,000 tons/day), many landfills are approaching capacity well ahead of initial forecasts. In most of these cities, space for new landfills remains limited or non-existent. For example, in 2020, the Philippines only had 10% of the 1,700 sanitary landfills needed based on forecasts prepared in 2000. In India, nearly 70% of its waste is dumped in landfills. Many of its largest cities lack proper space for new landfills. Based on 2017 estimates, India would require landfill space equivalent to 1,240 hectares per year to address its waste challenges adequately. Without meaningful waste reduction solutions, global solid waste-related emissions will rise to 2.6 billion tons of CO2e annually by 2050.

Top 20 Megacities 2010 – 2100e

2010 | 2050 | 2100 | ||||||

Rank | City | Population | Rank | City | Population | Rank | City | Population |

1 | Tokyo, Japan | 36,834,000 | 1 | Mumbai, India | 42,403,631 | 1 | Lagos, Nigeria | 88,344,661 |

2 | Delhi, India | 21,935,000 | 2 | Delhi, India | 36,156,789 | 2 | Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo | 83,493,793 |

3 | Mexico City, Mexico | 20,132,000 | 3 | Dhaka, Bangladesh | 35,193,184 | 3 | Dar Es Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania | 73,678,022 |

4 | Shanghai, China | 19,980,000 | 4 | Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo | 35,000,361 | 4 | Mumbai, India | 67,239,804 |

5 | São Paulo, Brazil | 19,660,000 | 5 | Kolkata, India | 33,042,208 | 5 | Delhi, India | 57,334,134 |

6 | Osaka, Japana | 19,492,000 | 6 | Lagos, Nigeria | 32,629,709 | 6 | Niamey, Niger | 56,594,472 |

7 | Mumbai, India | 19,422,000 | 7 | Tokyo, Japan | 32,621,993 | 7 | Dhaka, Bangladesh | 56,149,130 |

8 | New York-Newark, USA | 18,365,000 | 8 | Karachi, Pakistan | 31,696,042 | 8 | Kolkata, India | 54,249,845 |

9 | Cairo, Egypt | 16,899,000 | 9 | New York City-Newark, USA | 24,768,743 | 9 | Kabul, Afghanistan | 52,395,315 |

10 | Beijing, China | 16,190,000 | 10 | Mexico City, Mexico | 24,328,738 | 10 | Karachi, Pakistan | 50,269,659 |

11 | Dhaka, Bangladesh | 14,731,000 | 11 | Cairo, Egypt | 24,034,957 | 11 | Nairobi, Kenya | 49,055,566 |

12 | Calcutta, India | 14,283,000 | 12 | Metro Manila, Philippines | 23,545,397 | 12 | Lilongwe, Malawi | 46,661,254 |

13 | Buenos Aires, Argentina | 14,246,000 | 13 | Sao Paulo, Brazil | 22,824,800 | 13 | Blantyre City, Malawi | 41,379,375 |

14 | Karachi, Pakistan | 14,081,000 | 14 | Shanghai, China | 22,824,800 | 14 | Cairo, Egypt | 40,910,732 |

15 | Istanbul, Turkey | 12,703,000 | 15 | Lahore, Pakistan | 17,449,007 | 15 | Kampala, Uganda | 40,542,502 |

16 | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 12,374,000 | 16 | Kabul, Afghanistan | 17,091,030 | 16 | Metro Manila, Philippines | 40,136,219 |

17 | Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana USA | 12,160,000 | 17 | Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, USA | 16,416,436 | 17 | Lusaka, Zambia | 39,959,024 |

18 | Metro Manila, Philippines | 11,891,000 | 18 | Chennai, India | 16,278,430 | 18 | Mogadishu, Somalia | 37,740,826 |

19 | Moscow, Russian Federation | 11,461,000 | 19 | Khartoum, Sudan | 15,995,255 | 19 | Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | 36,371,702 |

20 | Chongqing, China | 11,244,000 | 20 | Dar es Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania | 15,973,084 | 20 | Baghdad, Iraq | 35,820,348 |

*Notes: Growth scenarios incorporate fertility, mortality, migration, and education rates expanding on the UN World Urbanization Prospects (WUP) framework.

Source: Hoornweg, D., & Pope, K. (2016). Population predictions for the world’s largest cities in the 21st century. Environment and Urbanization.

Solid waste management in many countries follows a standard pattern. Worldwide about 40% of waste is disposed of in landfills. Other solutions include recycling, composting, anaerobic digestion, incineration, and open dumping. Unfortunately, existing and inefficient solid waste models in many communities remain deeply entrenched, suggesting a business-as-usual scenario for the foreseeable future. At the same time, landfill stress intensifies, with up to 90% of waste in low-income countries openly dumped or burned. For many rapidly developing economies, future challenges will revolve around land use as the need to accommodate a rapidly urbanizing population takes precedence.

In developed markets, large-scale solutions are often deployed to address solid waste. However, large-scale solutions like waste incineration and landfill gas come with technical, health, and political challenges. Additionally, numerous instances exist where technologies deployed into emerging markets or Asia and Africa are not fit for purpose leading to white elephants. Any solutions that constrain the aspirations of many of these developing populations may be met with resistance from political leaders and other stakeholders.

Waste generation is positively correlated with income growth. Unfortunately, the path for growth and development for many countries across the Global South conveniently sidesteps effective solid waste management in support of highly ambitious growth targets. For example, countries like the Philippines and Vietnam have articulated aggressive income growth by 2050. The Philippines is targeting high-income status by 2040 as part of its Ambisyon Natin 2040 strategy. Concomitantly, Vietnam has targeted a 2050 per capita income target of $32,000 (8.6x current levels). Both countries are expected to be among the world’s top 20 economies by 2050. In Africa, countries such as Uganda, Tanzania, and Mozambique are expected to be among the fastest risers in the coming decades. The aspirational goals of the countries across Asia and Africa highlight an obvious problem with limited visibility on near-term and comprehensive solutions. Kicking the proverbial waste management “can” down the road will significantly affect these economic goals and their ability to strengthen climate resilience and develop sustainable cities for the future.

Solid waste management is a universal issue affecting every single person in the world.

Food Waste: A $2.6 Trillion Problem

Globally, the headline and “feel good” MSW stream often focuses on plastics. It’s a menace for sure, but recycling rates remain low. However, organics is a significant component of the MSW stream that remains sub-optimized. Organics is more of a “look in the mirror issue.” Food loss and waste is estimated at 1.3 billion tons annually, with a combined economic, social, and environmental cost of $2.6 trillion annually. Over 8% of greenhouse gas emissions are emitted across the food waste value chain. Close to 25% of the total 8% comes from food lost in supply chains or wasted by consumers. More broadly, greenhouse gas emissions from food systems exceed 33% of total anthropogenic emissions. A problem hiding in plain sight, it’s frequently overlooked and often gets lost in the climate change solutions debate. For example, in Australia, the amount of annual greenhouse gases from food waste exceeds that of the combined iron ore and steel industries. Recent studies suggest global food waste and loss may be twice what we initially thought.

Successfully addressing food loss and waste touches on various Sustainable Development Goals. These goals are SDG 12, SDG 6, SDG 13, SDG 14, and SDG 15. SDG 12.3 calls for halving per capita food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reducing food loss and waste among production and supply chains. How to feed an estimated 10 billion people by 2050 is becoming one of the foremost challenges of the 21st century. Dwindling arable land, lower crop yields, and increasing calorie consumption will pose substantial challenges to policymakers in the decades ahead. Food waste management in developed markets across North America and Europe constantly evolves within a developing ecosystem. Although results remain mixed. However, many of the strategies deployed in developed markets lack portability or scalability in emerging markets. Reasons vary but relate to cultural, fiscal, logistics, technology, etc.

The long-term macro socioeconomic trends underway across the Global South along with the current geopolitical flashpoints, will impact food security over the long term. Food supply infrastructure from production to distribution must be considered critical infrastructure akin to utilities, bridges, etc. Recent actions by the UAE and India on limiting food exports suggest the beginning of a disconnect in the food supply chain and a move to critical infrastructure status. With food demand expected to rise more than 50% between 2010 and 2050, it is clear that policymakers in megacities will struggle with these issues in the years to come. Recent improvements in the voluntary carbon markets and the evolution and acceptance of FLW protocols create opportunities and incentives to develop innovative solutions.

New York City’s Journey to Net Zero 2050

Like most large-scale cities, New York City faces future challenges brought about by climate change. Intensifying heat waves, storms, and rising sea levels pose social and economic threats to the city. More importantly, the city’s size, global economic importance, and socio-economic structure necessitate implementing policies to strengthen climate resilience to remain globally competitive. Key elements of the city’s profile include:

- The city’s population of 8.3 million makes it one of the largest cities in the developed world and part of a broader megalopolis of 23 million inhabitants.

- The city is ranked as the most diverse in the US with over 200 nationalities and 3.1 million immigrants. These immigrants, many of who come from megacities of the Global South, account for 37% of the city’s population and 45% of its workforce.

- The city’s position as a global and regional hub for economic activity attracts over 2 million daily commuters from Long Island and the bedroom communities of Connecticut and New Jersey.

- Its status as a global tourist destination attracts between 50-60 million visitors annually.

- Manhattan, one of its 5 boroughs, has a population density of 29,000/km2 making it one of the most densely populated urban areas in the United States. Smaller districts (community boards) in the city maintain higher population densities. For example, the Manhattan Community Board 3 is estimated at 31,183 people/km2

- New York City generates an estimated 14 million tons of waste annually, on par with megacities such as Mumbai, Lagos, etc.

In 2015 New York City was one of the first local governments to sign the Paris Pledge for Action. The plan called for adopting the Paris Climate Agreement, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and 100% renewable energy by 2050. Under the current Eric Adams administration, the city has continued its climate commitment through PlaNYC: Getting Sustainability Done strategic climate plan. The plan involves several initiatives, including improving building efficiency, strengthing coastal resilience, renewable energy and storage, and reducing waste and transportation emissions. Since 2007 the city has been engaged in strategic planning for climate change. Also, it became the first large-scale city to adopt climate budgeting, a process designed to factor climate impacts into the city’s budgeting. Aligned with the mayor’s office are key departments e.g. sanitation and the Office of the New York City Comptroller. The city’s comptroller serves as custodian of the city’s pension funds ($225 billion AUM), and its Chief Accountability Officer. The comptroller’s office recently developed a climate dashboard to ensure the city remains on track with its climate goals. As of April 2022, key findings from the comptroller’s office suggest that:

- New York City has reduced its emissions by 25% since 2005 with a 2050 goal to reduce emissions by 80% from 2005 levels.

- As of 2020 76.6% of energy consumption is fossil fuel-based gas and oil versus a 2050 target of 100% renewable energy by 2050

- The city’s 630 electric vehicle charging stations bring it nearly two-thirds of its goal of 1,000 charging stations by 2025

- The City’s pension funds have divested $2.8 billion from fossil fuels and invested $7.8 billion in climate solutions.

- Nearly 2.5 million New Yorkers live in the 100-year floodplain and low-lying areas that will become more vulnerable to climate change as sea levels rise.

NYC’s Waste Management Woes

New York City struggled with its solid waste issues for many decades due to rapid growth and limited space. Its last landfill, Fresh Kills Landfill, closed in 2001 after 53 years in operation but remained emblematic of the challenges facing a growing metropolis, high consumption, and waste accompanied by space constraints. The landfill, when closed, stood at 890 hectares. Most of the 14 million tons of waste generated annually is shipped to New Jersey and other states. Roughly 33% is classified as organic. New York City organic rates represent a relatively lower percentage of the MSW compared to other large-scale cities such as Dhaka, Bangladesh (78.9%), Accra, Ghana (65.8.%), Bogota, Columbia (61.5%), and Quezon City, Philippines (54%). Continued dependence on external locations suggests an out-of-sight-out-of-mind dynamic that exists to today. New York City’s ongoing challenges offer a cautionary tale for current and future megacities of the Global South as they grapple with growth, consumption, waste, and land use.

The Commercial Waste Zones Law

In 2019 the City of New York passed its Commercial Waste Zones Law. The legislation’s objective was to fix an inefficient commercial waste sector. It also targeted various program goals, including zero waste, worker rights, improved competition, environmental health, etc. Of particular interest was the recognition of the city’s food waste micro haulers and their inclusion in the stakeholder engagement process and final legislation. It highlighted the importance and value of these stakeholders and their significance in mitigating the adverse effects of one segment of the municipal waste stream, organics.

Key highlights of the law included:

- Zoned Collection: Dividing the city into 20 commercial waste zones, with each zone assigned several private waste hauling companies. This measure aimed to reduce the number of trucks on the road and improve waste collection efficiency.

- Exclusive Contracts: Waste hauling companies were required to secure exclusive contracts for collection within their designated zones. This aimed to create a more organized and regulated waste collection system.

- Environmental and Safety Standards: The law mandated waste hauling companies to meet specific environmental and safety standards in their operations. This included using cleaner and more sustainable collection methods and providing safety training for workers.

- Waste Reduction Targets: The law sets waste reduction targets for commercial establishments, encouraging them to adopt waste reduction and recycling practices to minimize the overall amount of waste generated.

It represented the culmination of the City’s pivot toward sustainability that began under the Bloomberg administration. The law was passed during the de Blasio administration and is being implemented under the current Adams administration. The city’s climate commitment continuity toward addressing environmental and social issues increases the likelihood of success in strengthening climate resistance to meet future challenges.

Microhaulers: Urban Frontliners in the Climate Change Fight

When passed, the Commercial Waste Zones Law provided a carve-out for the city’s microhaulers. The inclusion of these stakeholders represented a recognition of the part of the city of the importance of these micro-enterprises and their contribution to the city’s waste challenges. The law defines and classifies micro haulers as those who exclusively collect a certain annual tonnage of organic waste by bicycle of zero-emissions vehicles. Also, it set forth the framework for licensing while bringing the enterprise under the Business Integrity Commission, the city agency that relates the commercial waste sector and the public wholesale markets.

Specifically, the law defined micro haulers as:

Any person who does not dispose of waste at a solid waste transfer station and either (1) collects less than 2,600 tons of source-separated organic waste from commercial establishments per year and collects such waste exclusively using bicycles; or (2) collects less than 500 tons of source-separated organic waste from commercial establishments per year and collects such waste using exclusively (i) a zero emissions vehicle that has a gross vehicle weight rating of not more than 14,000 pounds or (ii) any other mode of transport specified in the rules of the Department of Sanitation. The law also set out requirements for managing the license, license term, fees, dispute resolution mechanisms, and liability e.g., insurance levels.

Including the micro haulers in the waste law solved significant challenges for multiple stakeholders. For the micro haulers, it formalized their role as part of the city’s waste ecosystem, allowing the evolution of business models and scaling to occur over time. The formalization stood in stark contrast to the informal models with no regulation or worker protections. For the City, it demonstrated its commitment to combating climate change and realizing environmental justice for more marginalized members of society. For commercial establishments, it provided better visibility on options for managing and disposing of organic waste through training programs offered by the micro haulers.

Although the city suspended the program during the pandemic, in 2022 the city awarded the first micro hauler license to Common Ground Compost. The company focuses on niche market segments, such as office buildings recovering from the pandemic. While it’s still early days for the waste law, we remain optimistic about the micro haulers’ outlook. A framework of formalization and an operating model has been set. Going forward, innovation (business model, technology, etc.), partnerships, and execution will determine their long-term success.

Over 2 billion workers, or over 60 percent of the world’s adult labor force, operate in the informal sector -at least part-time… On average it represents 35% of GDP in low and middle-income countries versus 15% in advanced economies.

Lessons for Megacities and Microhaulers in the Global South

Microhauling is by no means a new concept. It exists everywhere in some form across many societies worldwide. Moreover, the informal waste sector, prevalent in many emerging economies, remains a vital part of the waste management ecosystem as many waste pickers dig through mountains of trash searching for recyclables. Often marginalized in society, these workers suffer from poor living conditions and significant health issues, including cancers, respiratory, musculoskeletal, and other conditions. These workers continue to sit on society’s edges despite providing an invaluable service across many communities worldwide.

Activities of the informal waste sector differ but fall into a few general categories, including:

- Doorstep (household) waste pickers

- Waste traders

- Street waste picking

- enroute/truck waste pickers formal/informal

- Waste picking from dumps and landfills

In many communities across the Global South, the informal waste sector significantly contributes to city solid waste management efficiency through various activities. Many of these activities include collection, sorting, and processing of waste. Despite contributing to clean and sustainable cities, they face ongoing struggles with marginalization and recognition for their work. Waste pickers have successfully organized and won hard-fought recognition from municipalities in some countries. For example, waste pickers in the Asociación Cooperativa de Recicladores de Bogotá (ARB) represent roughly 1,800 waste pickers in the city. The organization has been fighting for recognition and fair treatment for several decades. In 2016 the Bogota government formally recognized the city’s waste pickers allowing them to secure additional compensation from the city. Today, Columbia is the only country in Latin America to officially recognize its waste pickers.

The New York City and Columbia examples demonstrate the benefits of developing a robust and scalable waste micro hauling ecosystem and the ability to achieve numerous sustainable development goals in both developed and emerging economies. Building effective micro hauling models offers many of the world’s estimated 15-20 million informal waste workers an additional and rapid path to sustainable prosperity.

Scaling Globally: Aligning the Ecosystem is Key

With urbanization rates rising, micro haulers’ value and leverage will only increase as communities seek cost-effective solid waste solutions. By 2035 more than 45 megacities will exist, up from 31 as of 2021. These megacities face a host of macro and micro threats, including urban sprawl, resource scarcity, corruption, GHG emissions, food and water security, and climate refugees. Presently, there are no solutions to address these threats comprehensively. Moreover, the speed of urbanization and middle-class growth continues to surpass policymakers’ ability to keep pace through regulations. Megacities are highly dense urban environments and complex ecosystems involving multiple stakeholders, including the informal sector, public sector, communities, individual citizens, and the private sector. Successfully scaling any solution requires elements of standardization and a robust and inclusive stakeholder ecosystem model.

Source: Wikipedia

Micro-Infrastructure Models: Structuring Streams of Value

Project ClearSky 2100 is developing solutions to strengthen climate resilience in the megacities of the Global South by developing micro-infrastructure models. Developing scalable pre-landfill models remains essential to combating food waste and resultant GHG emissions from megacities in the Global South. The current slate of megacity solutions is either single, non-circular, non-commercial, or not well suited for dense and rapidly evolving urban environments. These models should be technology and culturally agnostic, highly inclusive, and commercially driven, able to address multiple threats faced by urban environments. They should also eschew the grant-and-aid frameworks that usually suppress innovation, creativity, and value creation.

The Project ClearSky 2100 micro-infrastructure model is predicated on an integrated technology platform with organics recycling and micro haulers at its foundation. Food waste remains a high-value but underutilized waste stream that can aid soil fertility and produce animal feed, water, and energy when processed. ClearSky 2100 Ventures and Provectus of Canada are partnering to develop scalable platform models with additional technologies being integrated. Other technology partnerships include clean water, commercial EV charging, solar power, urban renewables, industrial gas production, and micro-scale carbon capture. Engineered social models are also being developed to integrate and align complex and diverse stakeholders. The platform aims for a 35,000-50,000 site rollout over the next several years, with PoC projects planned for Bangladesh, Columbia, Ghana, and the Philippines. For highly dense megacities, the Project ClearSky 2100 platform offers numerous advantages. These advantages include

- Designed for dense urban environments

- Multi-solution

- Socially engineered, inclusive, and ecosystem aligned

- Distributed and modular

- Disaster (geopolitical/natural) resilient

Final Thoughts: Exploring New Innovation Pathways

The rapidly rising urbanization rates in the coming decades are a worrying sign. In emerging economies, capital allocation often favors themes of growth and consumption while ignoring the underbelly of this growth. Urbanization, natural resource consumption, and biodiversity destruction remain inextricably linked. More than 90% of biodiversity loss is due to the extraction and processing of natural resources. The backslide on global circularity, the inability to achieve warming targets, and marginal progress toward sustainable cities are of more significant concern. New York City is a cautionary tale on the solid waste downside of decades of rapid and sustained growth. At the same time, it highlights opportunities created when multiple stakeholders within the city align to tackle various climate and social justice goals.

Solutions to address climate change continue to focus on nature-based solutions and large-scale white elephants. Numerous technologies are available to address the world’s environmental and climate challenges. Unfortunately, gaps in knowledge and awareness result in the inability to drive cross-border compatibility. Additionally, in emerging markets, inefficient economic structures, e.g., oligopolies, public corruption, and a focus on marginal solutions, e.g., loss and damage liability, will hinder progress on building climate resilience for the long term.

Technology alone won’t solve the world’s sustainable development and climate challenges, particularly those from urban sources. Significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the urban form requires broader stakeholder engagement, including citizens, the public and private sectors, and marginalized communities. In this regard, micro haulers must figure prominently in the debate with an equal seat at the table. Building scalable models for these stakeholders will provide significant growth opportunities and strengthen their ability to significantly improve the lives of all stakeholders in current and future megacities across the Global South.